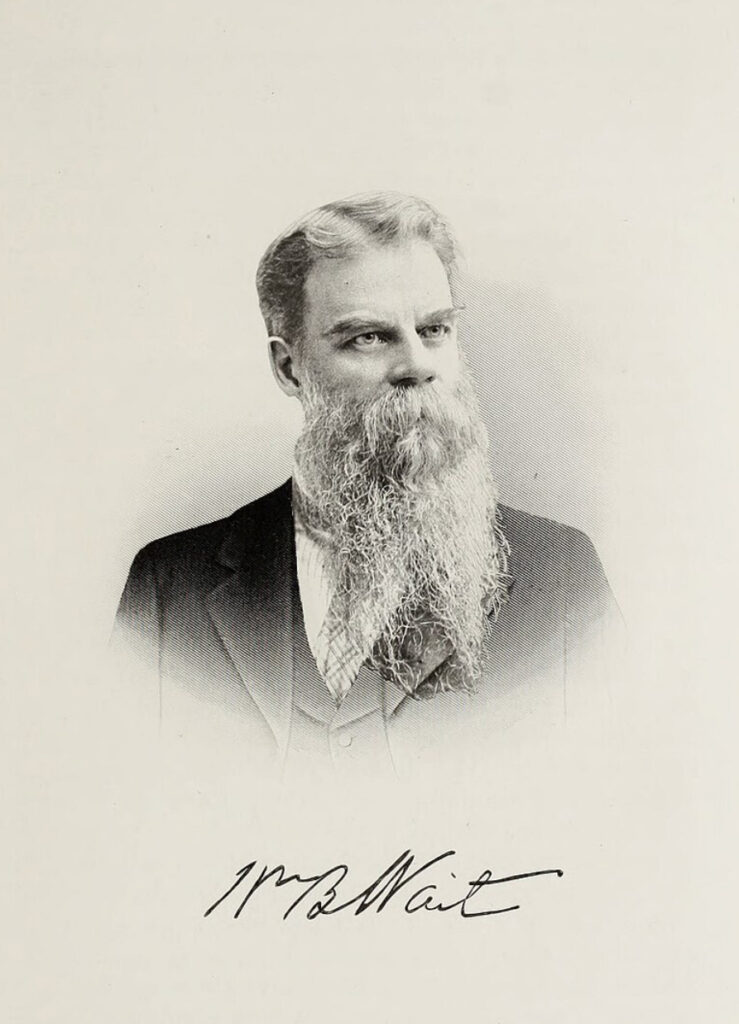

The Kleidograph was invented by William Bell Wait (1829–1916) while serving as the Director of the New York Institution for the Blind. The last image below is a remarkable photograph of students at the Institution using Kleidographs.

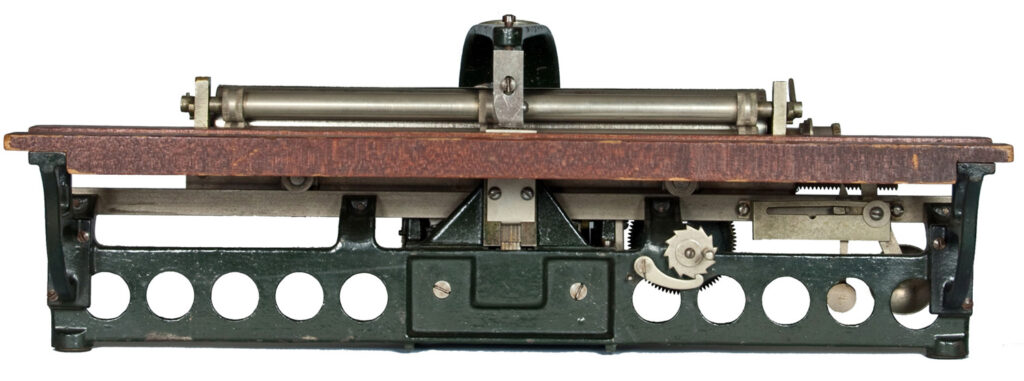

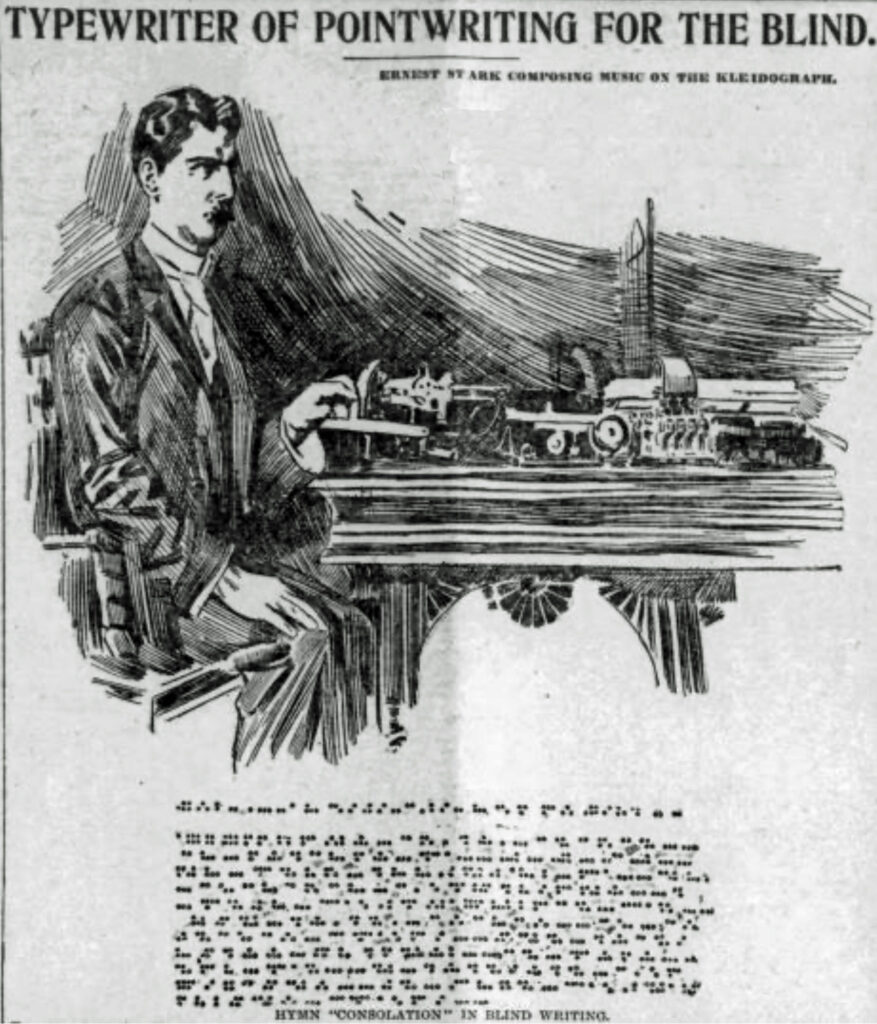

The Kleidograph was designed for typing in the New York Point System, an eight-dot system consisting of two horizontal rows of four dots each. William Bell Wait developed this alphabet and introduced it to the public in 1868, several years before the Kleidograph was manufactured.

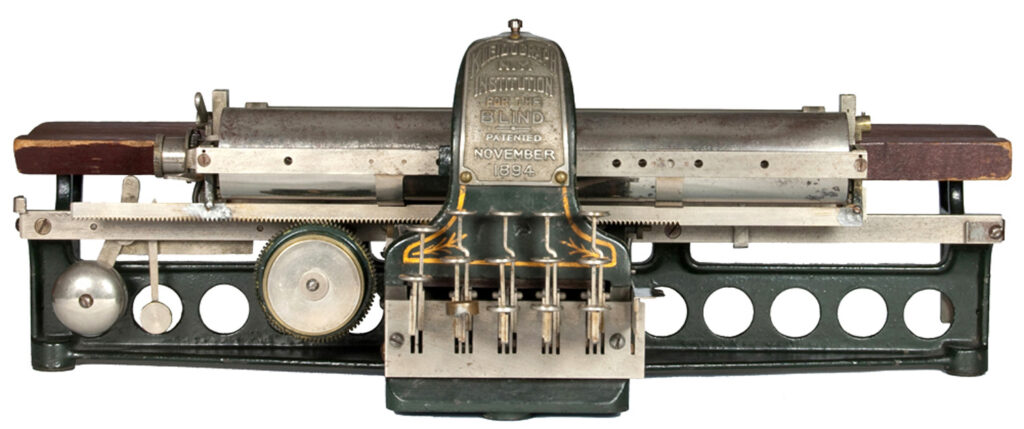

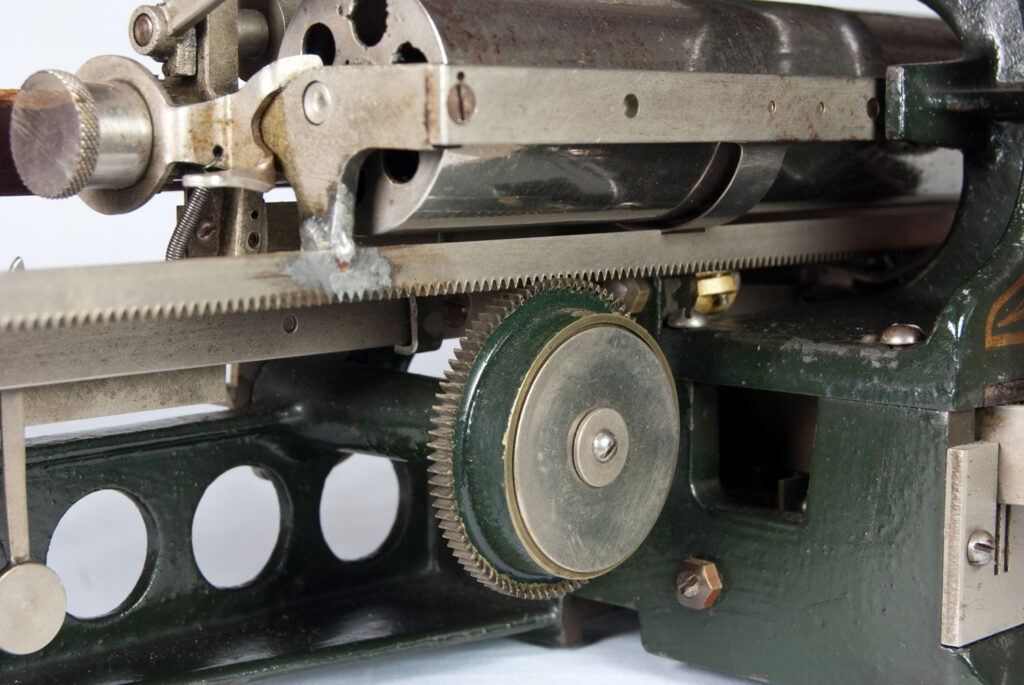

The Garvin Machine Company of New York began manufacturing the Kleidograph in 1894, producing an initial order of 100 machines for $1,250, with an additional $1,575 allocated for tools and dies. Few of these machines survive today. The company also manufactured the Crary typewriter and other index machines, including the Peoples.

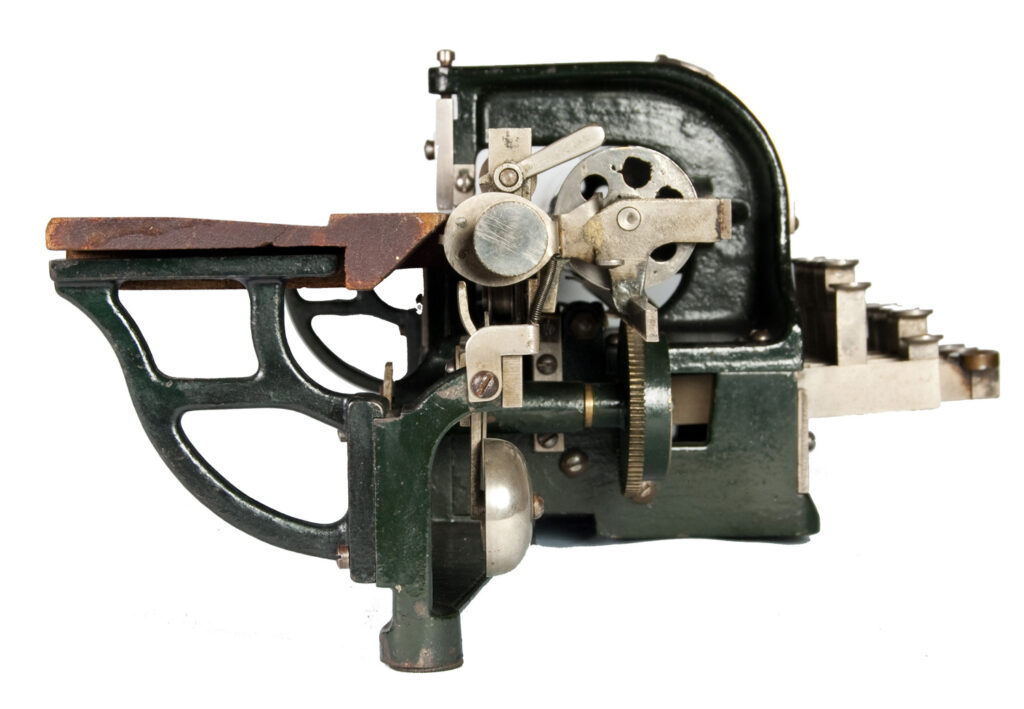

A key advantage of the Kleidograph over other contemporary typewriters for the blind was its ability to be operated with one hand (the right hand), allowing the user to read the raised dots with the other hand as the paper passed over the wooden platform behind the platen. This was made possible by a clever mechanism in which each of the four lower keys activated the two keys above, enabling the embossing of up to eight dots simultaneously. The two leftmost keys were designated for punctuation.

The New York Point System was widely used in American schools for the blind and served as the standard for typing and reading during the last quarter of the 19th century. However, over time, Louis Braille’s six-dot system gained global acceptance. Despite a fierce and much-publicized battle led by William Bell Wait and his supporters against proponents of the Braille system, including Helen Keller, the New York Point System ultimately became obsolete. Ironically, when Braille was officially adopted in the U.S., it became known as American Braille.