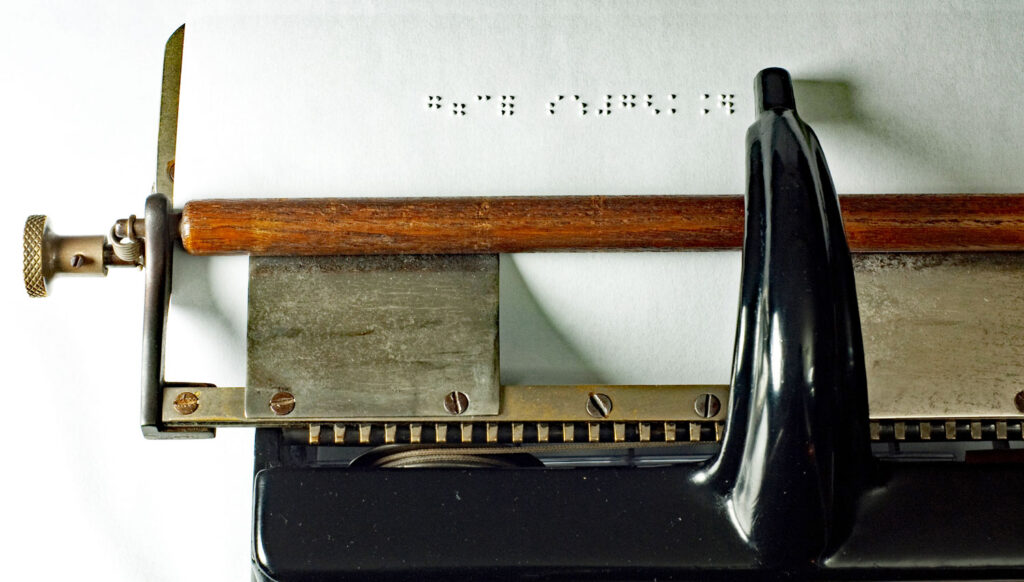

The Hall Braille-writer was invented by Frank H. Hall, superintendent of the Illinois Institution for the Education of the Blind. It was the first successful and widely used mechanical point-writer for the blind. Until this time, vision-impaired typists used a stylus and writing board, with the stylus embossing Braille dots in reverse onto the paper, requiring the page to be turned over for reading. Hall’s machine was a revelation, with its simple and practical design. The six piano-like keys could be pushed in any combination to create a Braille character in one action, using either one or both hands. The pins to emboss the paper came up from beneath, printing right side up, allowing the operator to read what was written as it was written. Importantly, this design eliminated the need to write in reverse. Typing a character in a single action of the hands allowed operators to write around 30 to 50 words per minute, a vast improvement over the stylus and writing board.

The six-dot Braille alphabet soon became the international standard and spelled the end of the Kleidograph, which used an eight-dot system.

In 1892, Hall had the skilled local gunsmith and metalworker Gustav Sieber make a prototype of his machine. Hall took Sieber’s prototype to the Munson Typewriter Company in Chicago, where superintendent T. B. Harrison and designer Samuel J. Seifried, inventor of the Munson typewriter, created six pilot models. Seeing the great potential of this revolutionary machine, Harrison and Seifried left the Munson Typewriter Company to start their own firm. They made an additional ninety-four machines based on the initial design. The Hall Braille-writers that followed this first group of one hundred were essentially of the same design, though there were variations, particularly in the carriage construction.

This Hall Braille-writer is serial number 25, making it the earliest known example of this historically important machine and one of only three known examples from the original group of one hundred.

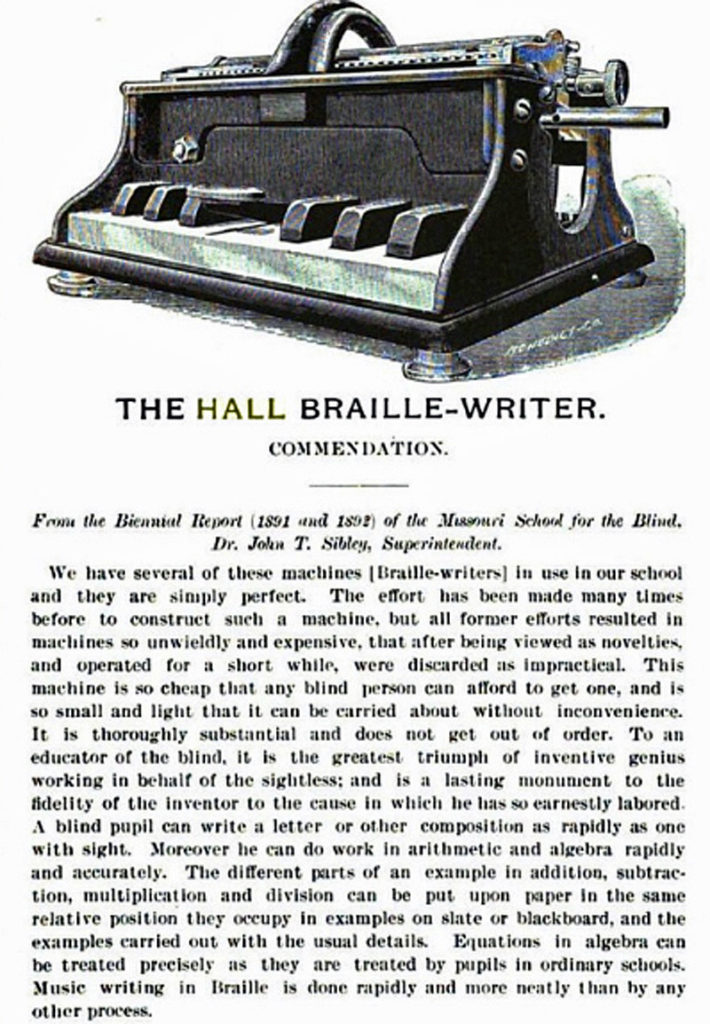

From A Brief History of the Illinois Institution for the Education of the Blind, 1849–1893.

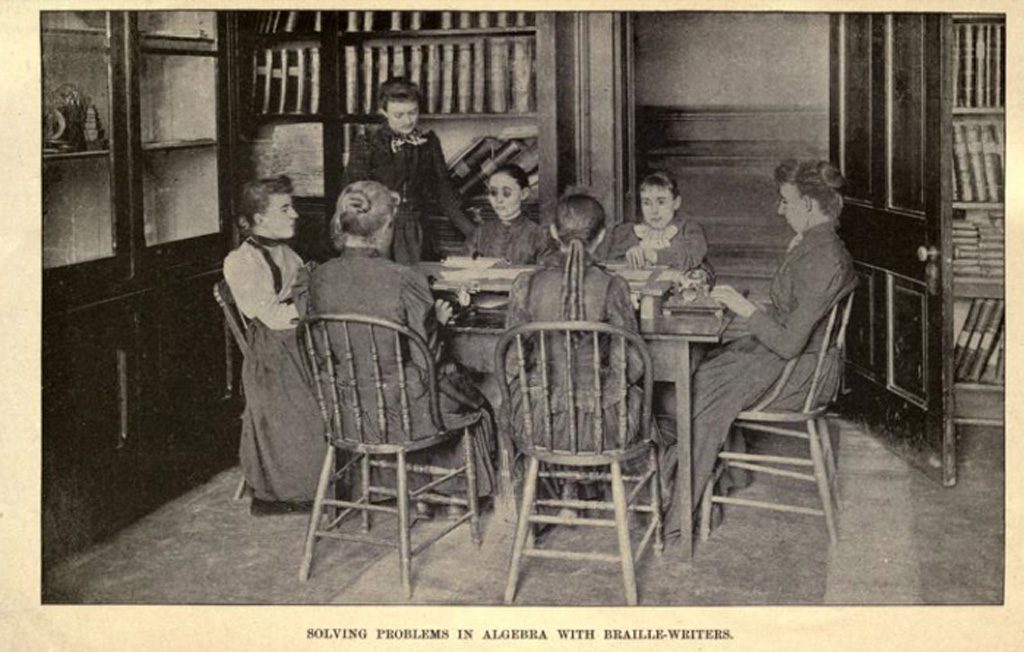

“Under the direction of the Superintendent, a machine for writing Braille has been constructed by which a pupil can write many times as fast as he could write with a ‘stylus and tablet’, with the further advantage of having what he has written in a convenient position to be read. With these machines the pupils solve their problems in algebra and write their letters and school exercises.”

Although the first machine was not completed till May 27, 1892, twenty-five are now in use in this institution, and about seventy-five have been contracted and sold to other institutions and to blind people. Fourteen are in use in the Boston school, nine in St. Louis, twelve in Philadelphia, six in Alabama, two in California, five have been shipped to England, and the remainder to private individuals in different parts of the United States.

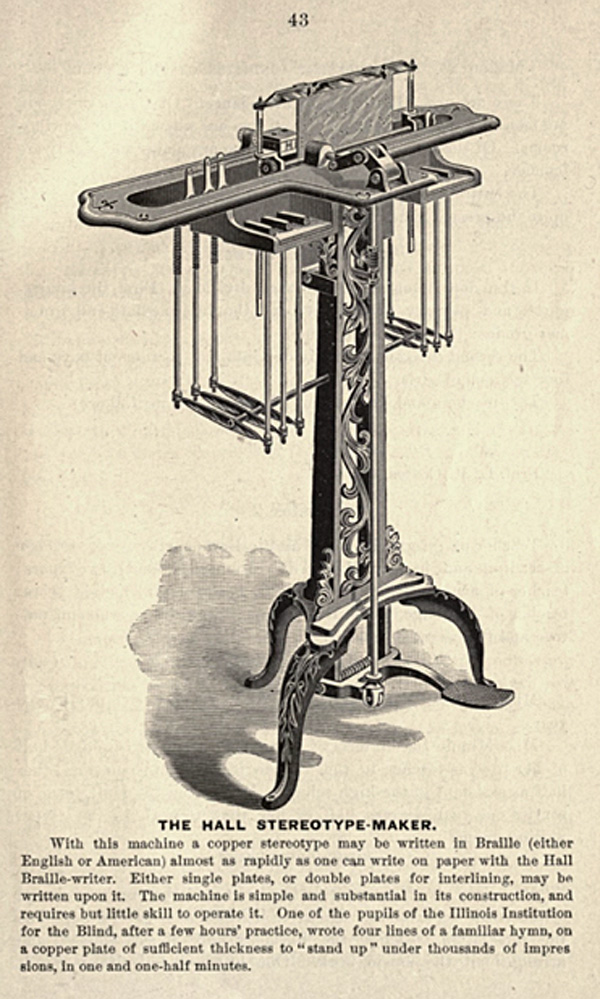

A machine has also been constructed, The Hall Stereotype-maker, (see illustration below) by means of which work can be written on copper plates. These plates can be used as stereotypes for printing with an ordinary press. Thousands of copies can be printed from each plate.”

Another rare period account can be seen below from the Missouri School for the Blind.

It is heartwarming to note that Hall’s motivation was not personal profit but a sincere desire to improve the ability of vision-impaired individuals to write. He chose not to patent his invention and ensured it was affordably priced, costing $10 to manufacture and sold for just $11.