A short video of the Caligraph 2 working.

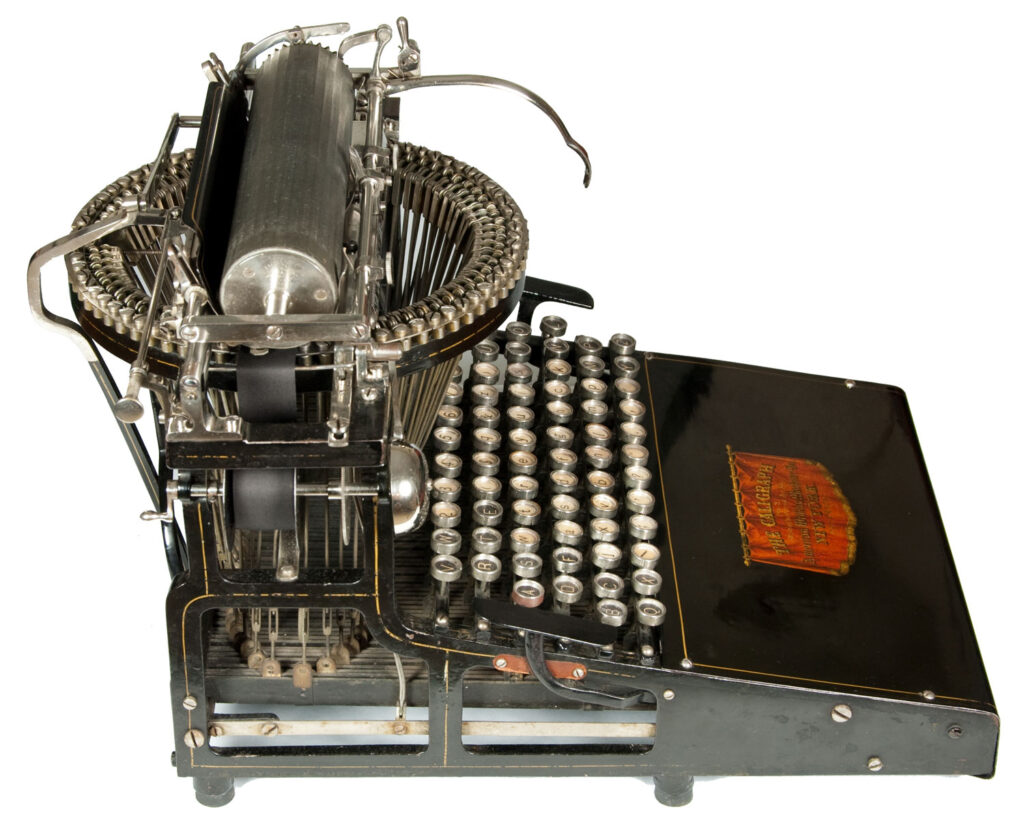

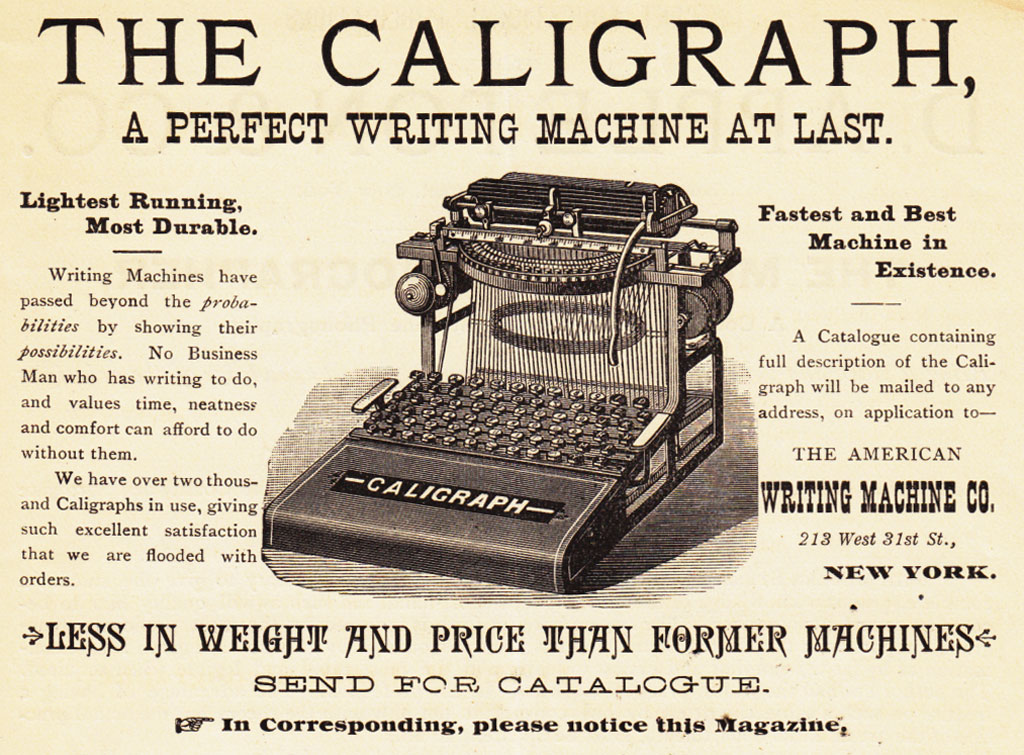

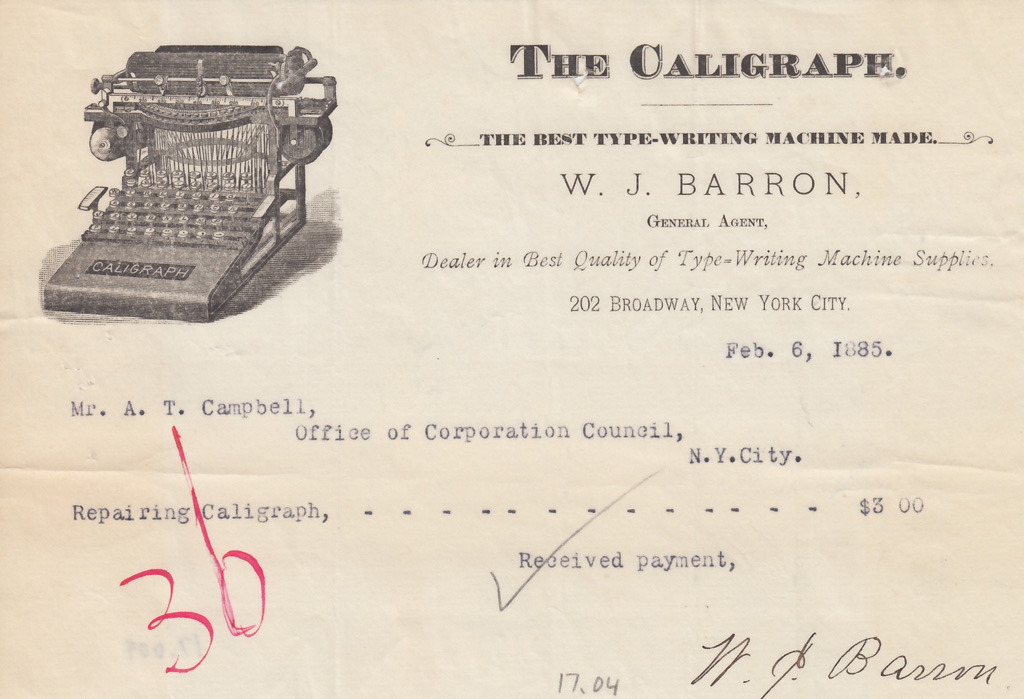

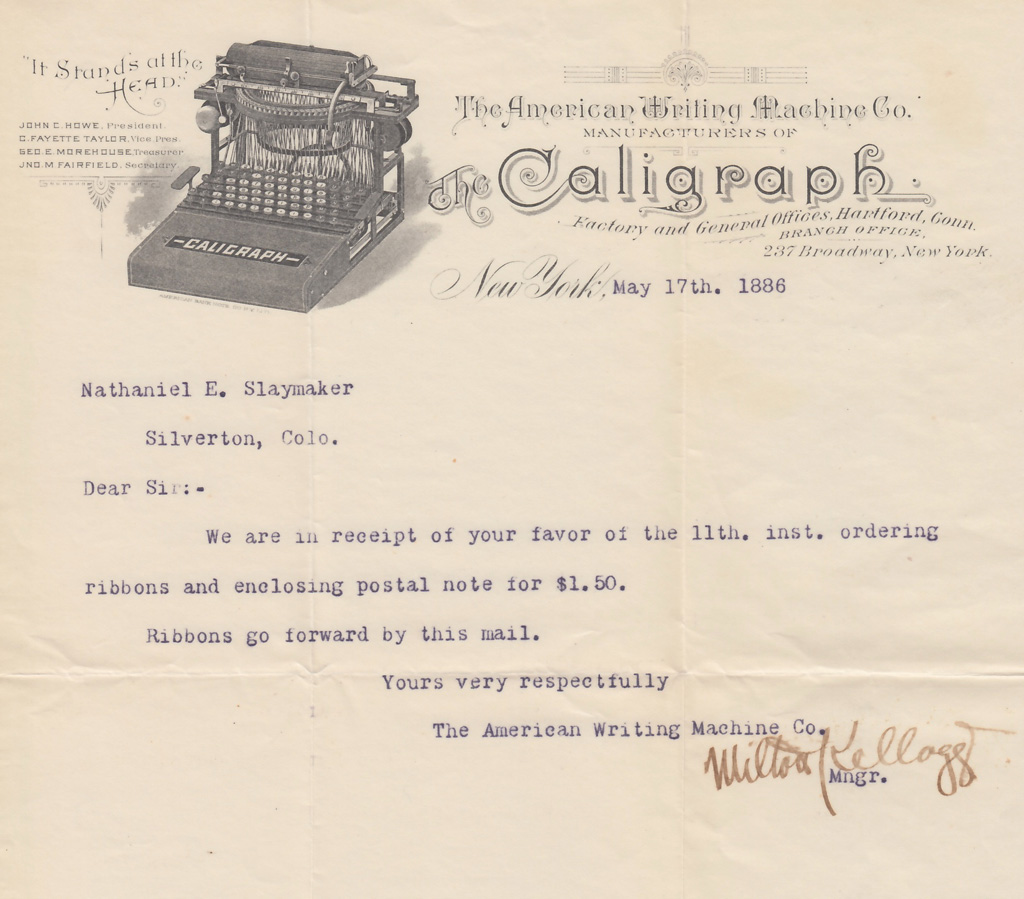

The Caligraph 2 was the first typewriter produced with a double keyboard. Without a shift key, it featured separate black keys for uppercase characters and white keys for lowercase.

A Scientific American article from March 1886 highlighted the perceived advantage of the double keyboard:

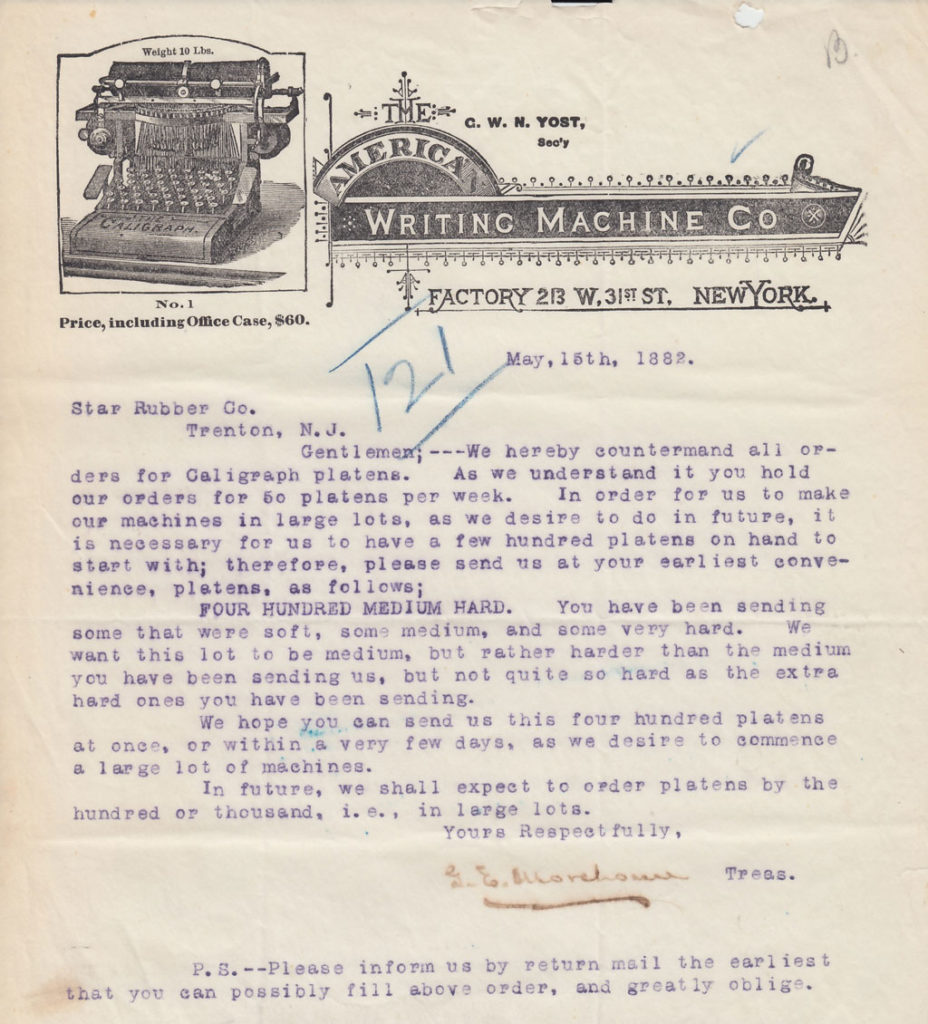

“Up to 1881, when the American Writing Machine Company introduced the Caligraph, double case writing machines were incomplete, being so constructed as to compel the operator to shift the carriage by a gratuitous stroke for capital letters and figures. The Caligraph prints each character in both capitals and small letters at a single finger stroke.”

Many other double keyboard typewriters would follow.

Double keyboard machines began to lose favor only after touch typing, with the home row as a reference point, gained widespread acceptance in the 1890s. A celebrated typing contest in 1888 between Frank McGurrin, using a Remington 2 (the first typewriter to feature a single shift keyboard, introduced in 1878), and Louis Taub on a Caligraph 2, marked a turning point. McGurrin won decisively, demonstrating the advantage of home row positioning, which allowed typists to maintain finger placement without glancing at the keyboard.

The “gratuitous stroke” required to shift on four-row keyboards turned out to be less significant than the overall advantage of speed and efficiency. Ironically, Remington continued producing a front-strike double keyboard typewriter, alongside their single keyboard models, until around 1913 with the Model 10.

Like its predecessor, the Remington, the Caligraph is a “blind writer,” with typebars that strike the underside of the platen. Text remains hidden until the page advances a few lines, or the hinged carriage is lifted to reveal the underside.

In the first image below, note the platen’s longitudinal facets. This design ensured full contact with the flat heads of the typebars. Later models featured smooth, round platens after manufacturers began grinding subtle curves into the typebar heads.

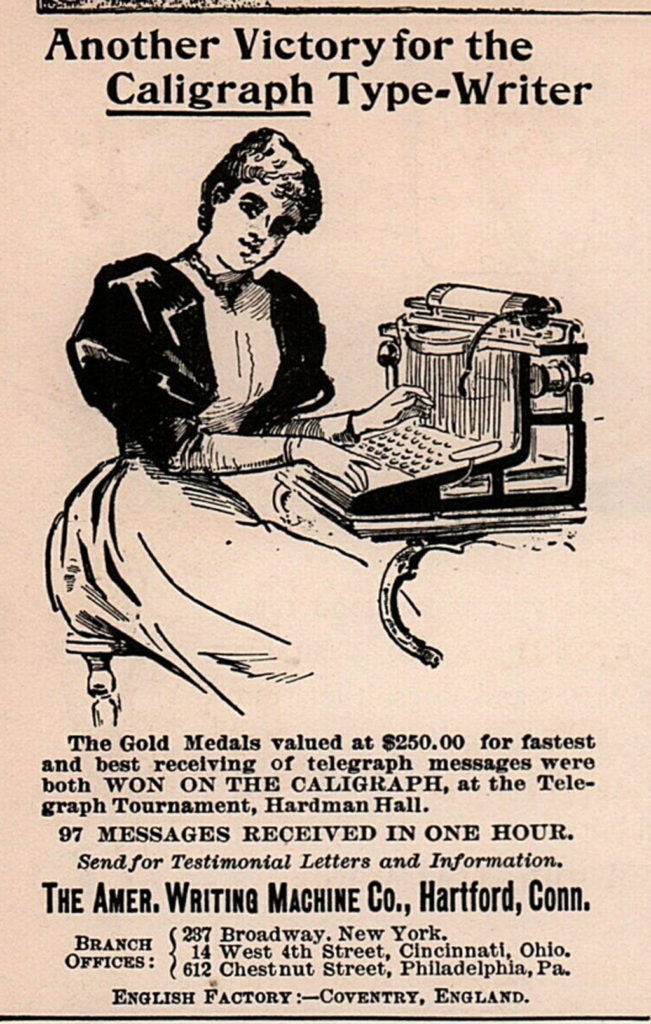

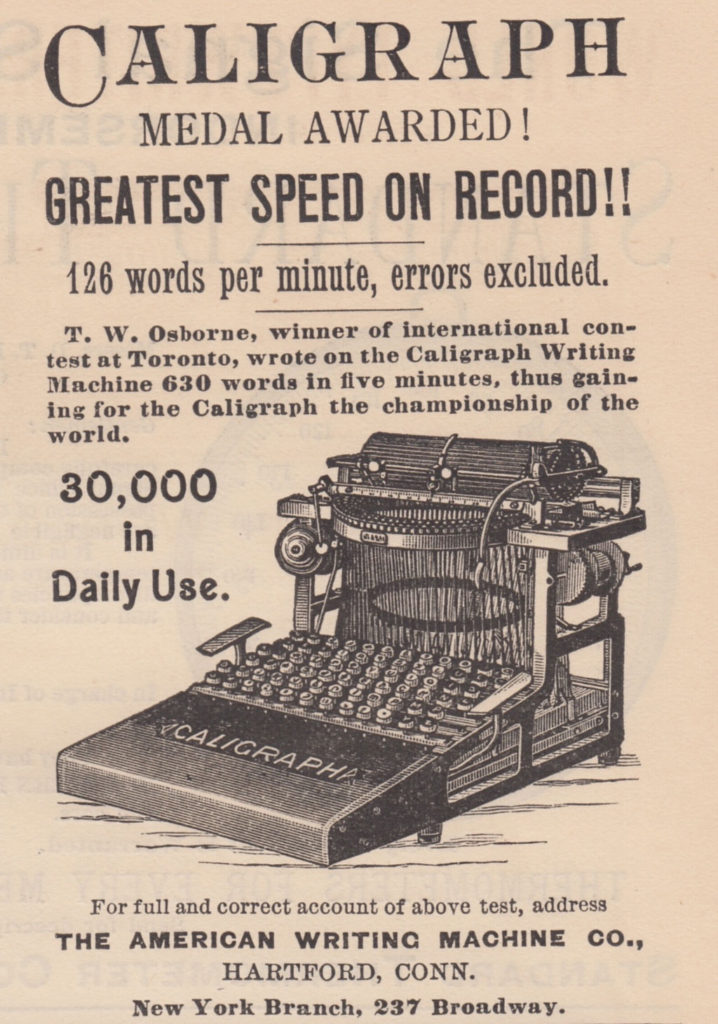

It might be hard to believe the following claim publicized in 1889. “GREATEST SPEED ON RECORD!! T. W. Osborne wrote 179 words in one single minute, and G. A. McBride wrote 129 words in a single minute, Blindfolded, on the Caligraph.”